In the last 25 years I’ve had 3 bouts with cellulitis. All three necessitated long stints of IV antibiotics which until recently meant day time treatments M-F in outpatients and evening and weekends in Emerg. There would come a point when I wasn’t feeling so terrible anymore and I would start to find the experience fascinating. I know, weird eh? I am still friends with some other patients and with some of the nurses I met during the last two runs. Before renovations which made the ER all white and shiny and much more private it was an amazing place to watch human interactions. I used to know who was on triage when I walked in just from the anxiety levels in the waiting room. There were a couple of nurses who were incredibly skilled at calming people down and even making us laugh in the midst of our suffering. I decided that I should have gone into medical sociology when I did my uni studies as there really is nothing more interesting to study. I could have done my field work in ERs!

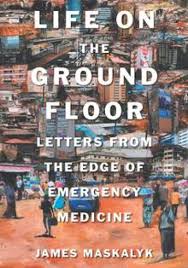

One of the things I grew to love about going to the hospital three times a day was all the time I had to read. My fascination with the place also lead to my reading lots of medical memoirs and it is a big field. Brian Goldman’s The Night Shift, Tilda Shalof’s The Making of a Nurse, and Victoria Sweet’s God’s Hotel are my three favourites in that genre. My 14th book in this project is James Maskalyk’s Life on the Ground Floor: Letters from the edge of emergency medicine and it will go on the shelf next to others as a great read. Maskalyk alternates between working in Toronto and Ethiopia and weaves together stories from both with stories of his grandfather who lives in northern Alberta. It’s a very moving book that seemed to me to be a meditation as much on dying as on healing.

I’ve been thinking about this book since I finished it. One of the things I find fascinating about it is that while there are obviously big differences between emergency medicine in Toronto and Addis Ababa what struck me was the similarities. In both situations it is Maskalyk’s connection to patients that is front and centre. And in particular, it is his ability to remain present to his patients even in the presence of suffering and their dying that moved me. He describes the signs of burn out when indifference and anger become the attitude of staff towards patients. It struck me how this parallels in some ways the experience of ministry when clergy begin to feel manipulated, or criticized, or taken for granted and begin to resent the people they are called to serve. But while Maskalyk may say, it is time then to quit, he’s actually very understanding of the struggles to stay healthy in medicine (and I suspect “helping” professionals generally). Certainly there are unique aspects to the kind of intensity he experiences in his work and particular issues in working shift work (he talks about the dangers of self-medication to get to sleep and to wake up) but there is a lot of wisdom in his observations for anyone struggling with compassion fatigue or secondary trauma.

At one point Maskalyk talks about how in addition to the worries docs start taking the numbness home too. He says that joy starts to seem like it is for fools because in the end all of us will die. This made me think of Caleb Wilde’s comments about being risk averse and overly protective of children because of the awareness of how badly things can go. A friend of mine, a funeral director, asked me once, when I was really cautious about walking down a dock to get into a boat, if I had always been this scared of the water. No I said, I grew up on boats and around water. I’d become this way after 20 years of doing funerals. Working with post-secondary students too many of the services I’ve done have followed tragic deaths. It is easy to become obsessed with the fragility of human life and to begin to resent people who seem blissfully unaware of how quickly their lives can change.

There is a line in the film version of Shadowlands in which a student says to C.S.Lewis, something to the effect of “I read to know I’m not alone.” I felt often reading this book, despite living and working in very different circumstances, a sense of recognition. In an incredible poem entitled “fuck you ee cummings”, Ron Currie writes:

when you’re a writer people sometimes ask

why you decided to be a writer

insofar as there’s any answer

the thing i’ve settled on is that

writing is an act of faith

the faith that you and i love the same things

fear the same things

grieve the same things

no matter that i am a man and you are a woman

or that i am white and you are latino

or that i am american and you are afghani

faith, in short, that love and fear and grief are the same thing everywhere

and the rest is just details

and that if i write about the things i love and fear and grieve,

you will see yourself in me

and vice versa

and having looked in the mirror

and seen ourselves rendered strange yet recognizable

we will be less lonely and afraid and angry

and less inclined to want to kill each other

and less likely to dismiss each other’s suffering

maybe.

Maskalyk is a really good writer.